Eating the Elephant One Bite at a Time

“It feels inefficient.” “It takes a lot of effort,” the experts say.

But being there upstream to deliver on health equity pays off.

Picture a 50-something man working an hourly job that doesn’t provide health insurance. Say he lives in a food desert. He’s got high blood pressure and is on the verge of diabetes. Yes, he knows he needs to address his health issues, but paying for medical care plus taking time off work is costly for him. Surefire bet: Within five years he’s in the ER suffering from a heart attack. He’s away from work and family, facing mounting bills and dwindling income.

Had society stepped in early with resources and support, his health crisis and the ripple effects on his family, his community and society at large could have been mitigated. Now replay this story thousands or millions of times across America.

So, yes, it may seem inefficient to jump in upstream of the rocks. But it’s both morally right and necessary.

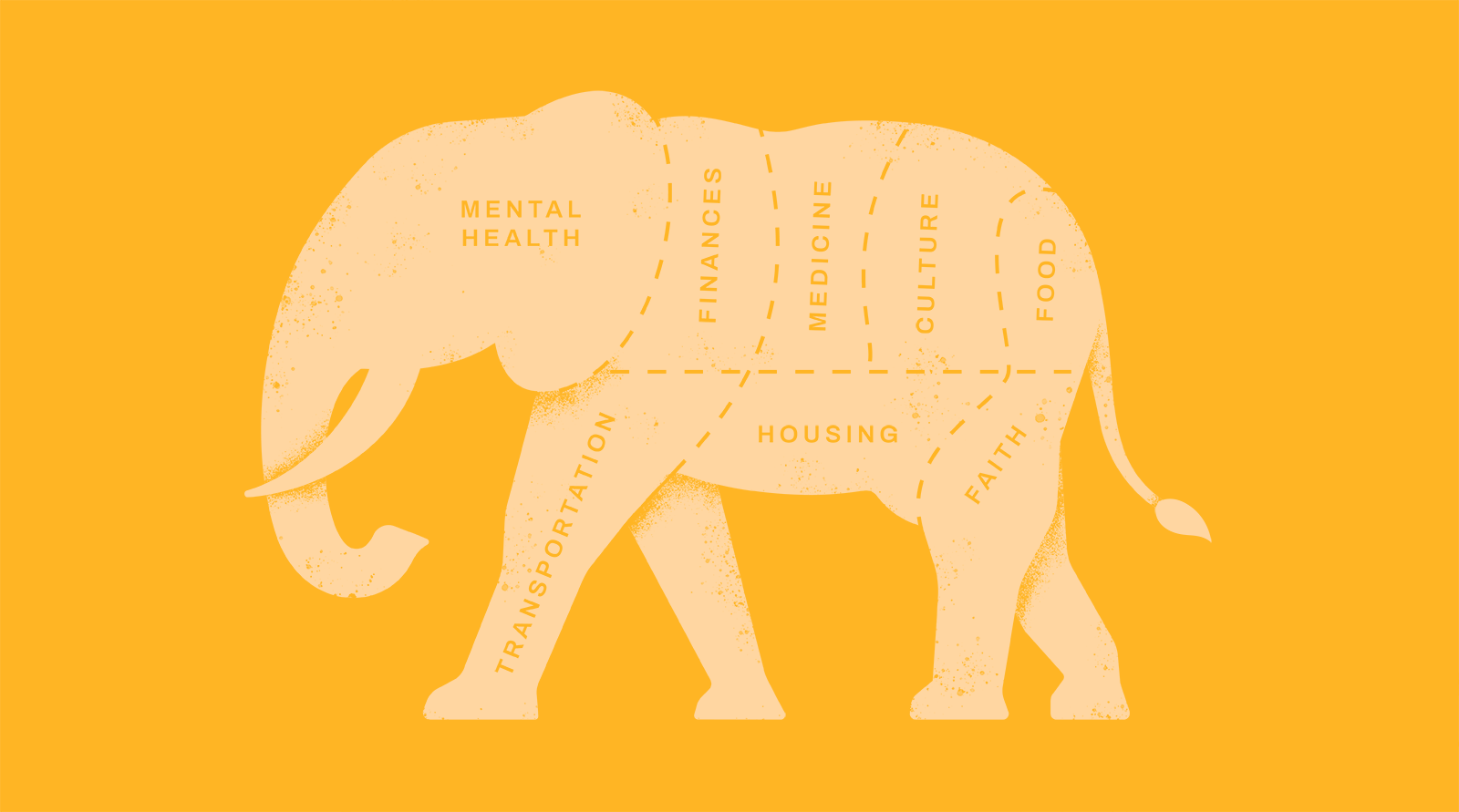

Issues of poverty. Of race. You’ve seen the data, the glaring discrepancies. Dealing with the factors affecting one person’s health and wellbeing is tricky enough. But population-level work and addressing systemic societal problems that prevent equity… it’s been left for the dreamers.

Or has it?

Despite the flaws in our system, many are working to flip the script. They’re meeting people where they are and designing less-efficient-but-more-personal programs to achieve greater outcomes.

They’re moving the needle. And here are their stories.

Getting Ahead (A Head?) on Physical Health

Parrish

Jarod Parrish’s patients visit with him from a barber’s chair, not an exam table. The pharmacist is improving the health of Black men in Nashville by screening them for hypertension when they come in for a cut. It’s part of an ongoing clinical study modeled on a project in Los Angeles.

“It’s in the back of your mind: ‘I should really check my blood pressure and eat better.’ And then as time goes on, you’re juggling so many things in life and some of them fall.” That’s how Parrish, PharmD and a clinical research pharmacist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, describes the underlying barrier to care among the patients he sees.

Similar previous studies have had notable success in detecting, treating and controlling hypertension among Black men. One of the keys has been education from a clinician at the point of care. Parrish noted that in the first iteration of the study, in Texas, barbershop patrons with high blood pressure were provided literature and recommendations to follow up with a specialist. “People wouldn’t stick around very much at that point,” said Parrish. But once pharmacists were included in the Los Angeles iteration, the team saw a drop of 20 points in patient blood pressure. Participants were nine times more likely to achieve hypertension control than those on “usual” care.

Mind and Body

Wenneker

It happens every day: A person comes into the primary care physician’s office experiencing a physical ailment, but it’s either a manifestation of underlying depression or made worse because of the depression.

Mark Wenneker, MD, a primary care internist, principal and behavioral health segment leader at The Chartis Group, has been working with health system clients to integrate behavioral health clinicians within primary care offices, a model known in the industry as Collaborative Care. The basic concept? To add behavioral health services and expertise where patients already are and with clinicians they know and trust – namely, their PCP. Problems can be identified earlier, and necessary services can be provided and coordinated without having to push patients to another location or care team.

“There’s a wealth of evidence that integrating behavioral health and primary care improves outcomes such as depression scores, patient satisfaction and provider satisfaction,” Wenneker said. In addition, studies have “demonstrated that there’s a reduction in total cost of care that includes both inpatient and outpatient care for medical conditions.”

Trust. Always Trust

The success of these programs isn’t just about showing up where patients already are. It’s about trust – a key element to the Art of Change.

Okafor

“People are more trusting of their barbers,” observed Henry Okafor, MD, a Vanderbilt University Medical Center cardiologist and researcher on the barbershop clinical trial team. “They follow their barbers for a long time. So, if the barber is saying ‘Trust this pharmacist,’ they’re willing to participate.”

Parrish said it doesn’t take long to develop that trust. “At that first screening visit they’re usually feeling us out,” he noted. “Then the barber explains what we’re doing and says, ‘Go, get your blood pressure checked.’” By the second visit, the trust is there. The barber serves as the bridge by saying, “We want you to be healthier, we want you to be around longer so we can cut your hair longer.”

And once those barriers come down, Parrish said it’s amazing how much individuals want to know about their health.

Mental, Physical and Spiritual

Few voices are more powerful than clergy, particularly within minority communities. And when you marry ministry with healthcare, you gain awesome influence.

Walker

“The church is the pillar, specifically in the African-American community,” said Stephanie Walker, MD, a neonatologist, founder of ChurchFIT, a fitness and health awareness program, and leader of the Mt. Zion (Baptist Church) Health Care Ministry.

In her roles as a physician, health ministry leader and spouse of a clergyman (her husband is bishop of Mt. Zion), Walker has a holistic view of individuals and is uniquely positioned to serve as a bridge. Because the church is integral to community life, especially within Black communities, “it must be involved in health,” she said. A quick scan down the list of ministries at Mt. Zion bears this out. Aside from ChurchFIT, the church hosts a food pantry, offers health and wellness services, coordinates with Meals on Wheels and more.

The other piece involves trust and influence. By collaborating with trusted faith leaders, healthcare providers can gain trust with communities of color that can effectuate a healthier population. Without that transfer of trust, Okafor and Parrish said even best efforts to help people in those communities to improve their health won’t get very far.

“It’s critically important for the medical community to understand the influence of the faith community and underrepresented minorities lives,” said Walker. “People are putting out programs and PSAs that are falling on deaf ears because you’re not involving the people that these communities listen to.”

Instead, said Walker, healthcare providers should go to influencers and ask, “How do you feel your congregants would receive this? Because the bottom line is, if the pastor doesn’t buy into it or say it, repeat it or support it…Guess what the people are hearing? Not the message you want them to.”

Making Care Productive

Parrish and Okafor assert that most chronic diseases can be evaluated in the context of alternative sites of care. Rather than trying to push people to a doctor’s office for screening, a broader, more holistic model is one in which the clinician goes to people to have a casual conversation that provides education and empathy. “People already talk about high cholesterol and diabetes at the barbershop,” said Parrish. He can simply join the conversation, provide some education and guide people to the next steps if needed.

But what happens to the holistic model when follow up care is needed?

For one physician, the sound approach is to be less reflexive and more evidence-based to cut down on unnecessary procedures, which are expensive and stressful to patients.

Heller

Richard Heller, MD, MBA, a radiologist and associate chief medical officer at Radiology Partners, a national radiology practice, thinks a lot about reducing waste in healthcare. “If we consider healthcare a precious resource, we want to take actions that reduce waste, such as limiting low-value care,” he said.

Take chest and neck scans. When doing CTs of the area, you usually see the thyroid gland, so radiologists will naturally review it. Turns out, nodules in the thyroid gland are very common and very often harmless. Even so, many radiologists reflexively refer those patients for further assessment. That can mean more exams, referral to specialists, additional bills and greater stress for the patient, he concluded.

Since the majority of nodules aren’t a problem, Radiology Partners has developed a program to help physicians use evidence-based guidelines and temper the reflex to refer. “Our best practice recommendations, based on existing evidence-based guidelines, help our radiologists evaluate thyroid nodules using specific criteria and then give a recommendation based on the evidence,” said Heller. “If the nodule doesn’t require follow up, put that in your radiology report and end it right there. But if it does, tell the referring physician exactly what needs to be done and when. Be clear. Ambiguity leads to variability, and variability is the calling card of waste.”

Sure, it might be easier for the radiologist to be vague and leave the door open for additional exams, but the result is lower value care, negatively impacting both patients and the healthcare system.

Getting There

These stories – Heller’s emphasis on evidence-based care, Okafor and Parrish’s blood pressure cuff, Walker’s faith-fueled medicine – are changing healthcare for the better.

But how do we scale up?

How do we support people so they can receive and absorb and implement the care they need, whatever that looks like?

No matter how much trust people have in the influencers, how much interest they have in their health and how committed clinicians are to providing personal, evidence-based care, it won’t happen without a holistic view of the circumstances people are dealing with in the moment they need help.

The first step is basic: Pointing people in the right direction.

“Many people don’t even know where to start,” Okafor said.

From there, providers need to account for the factors that could prevent people from moving forward. Walker recalled a class she attended during her time at Harvard. A man was speaking about a program he was establishing in the inner city to help address diabetes and hypertension. His plan looked good on paper. But when his team sat down with people from the community, those community members posed the hard questions about housing and education and the economic impact. Even more compellingly, the speaker said he and his team were asked, “Can you make sure Ms. Susie can turn on her lights because if she can’t turn on her lights, she’s not spending $20 on her diabetes medicine.”

The result was a program that wasn’t just about “science.” It included vouchers, a partnership with the electric company and other social organizations. As those needs were addressed, the medical team and, more importantly, the people they were serving, “could finally pay attention to the medical side of things,” Walker recalled the guest speaker saying.

And maybe that’s the lesson. Maybe providing quality, holistic care isn’t that complicated and isn’t as inefficient as it feels. Maybe we’ve just overengineered the system, allowing layers of technology and fee-for-service incentives to get in the way and cloud our perspective. Maybe it’s time we think less about all the “extra” hard things we need to do to get people the care they need and see it as removing barriers instead of doing more.

Parrish, for one doesn’t claim that his work is easy. But making the effort of showing up rather than waiting for people to come to him? That is.

“It doesn’t take that much work to go to people,” he said.

And the payoff is huge.